Alternative control process for VOC

For those who apply a wet surface coating to a product and make business and process decisions to dryHere are a few factors to consider:

1. Product quality requirements

2. Security

3. Regulatory and Air Quality Restrictions

4. Cost

5. Ease of operation and reliability

Process alternatives include the following:

1. Reconfigure

A. Transition from solvent-based to water-based wet formulations

B. Conversion to a high solid dosage with little or no volatile components

2. Vapor destruction

A. Thermal oxidation of organic compounds produces carbon dioxide and water vapor

B. Catalytic oxidation

3. Vapor recovery

A. Absorption-desorption using activated carbon

B. Direct vapor condensation

Rewriting has been the subject of a great deal of research and is beyond the scope of this chapter.

There has been a lot of success, but in many cases, the use of volatile organic compounds can provide a good end product quality or advantage. The safety of handling solvents and costs needs to be checked.

Vapor destruction or oxidation typically requires less capital expenditure than vapor recovery, but the additional cost of a recovery facility may be justified if a significant amount of solvent can be reused,

Reduce the need to purchase new solvents every year. If oxidized, some heat energy can be recovered from the solvent, but in all cases, additional energy needs to be purchased to operate the vapor oxidizer.

In the case of solvent recovery using carbon adsorption-desorption equipment, the cost of recovering the solvent is often higher than the cost of purchasing a new solvent; This additional cost is justified by the need to avoid air pollution.

No control process is applicable in all situations. It is necessary to consider specific cases to determine which are the preferred options. Typically, however, thermal oxidation will be preferred for smaller vapor emission rates or where the solvent cannot be reused, and catalytic oxidation is only considered if the gas flow required to capture the flue gas results in a relatively low vapor concentration. If larger quantities of vapor can be reused and a new dryer can be planned, solvent recovery by direct vapor condensation will be preferred.

1. Safety

Process safety when handling volatile organic compounds requires methods to ensure protection against fire and explosion damage.

The usual procedure for applying and drying solvent-based paints is to purge the organic vapors under an excess gas stream so that the vapor concentration is too low to sustain combustion if the ignition temperature rises.

Typically, at least 300 to 400 volumes of air are used to dilute one volume of vapor so that it cannot be ignited, and it is not uncommon to use thousands of volumes of air per unit volume of vapor.

However, it should be understood that fire and explosion hazards can also be controlled by keeping the oxygen concentration too low to sustain combustion. Ordinary solvents do not ignite or burn continuously in atmospheres with less than 10% to 13% oxygen (relative to air containing 21% oxygen). This control procedure is the key to an economical condensate solvent recovery process.

2. Operating costs

The cost of controlling steam emissions is highly dependent on the amount of air mixed with the steam. Excess air can provide the benefit of greater safety and/or a higher rate of vapor capture in a fume hood, but excess air greatly increases the cost of removing steam from the air.

In industrial operations that include steam incinerators or vapor recovery systems, it is important to minimize the flow of dilution air to the extent that safety is not compromised. For example, toluene vapor with a concentration of less than 1.2% vapor in the air is too thin to sustain combustion if ignited, while toluene vapor above 7.1% is too high to sustain combustion if ignited. These limits are called LEL (Lower Explosion Limit) or LFL (Lower Flammability Limit), or UEL or UFL as the upper limit. Limits are slightly different for other solvents, which apply to "normal" dry conditions up to 200°F.

It is common practice to ensure that the dryer exhaust flow does not exceed 25% LEL (four times the safety factor) to minimize the risk of combustible mixtures within the dryer. The National Fire Protection Association's standard will allow vapor concentrations to "not exceed 50% of the LEL," as long as continuous indicators and alarm settings are scheduled to shut down the system at lower wet points. However, when the average exhaust concentration is in the range of 40 to 50% LEL, there is no guarantee that a higher concentration will not exist within the dryer. Relatively few dryers typically operate with LEL vapor concentrations of 40% or higher.

On the other hand, when printing is applied to a small set of surfaces, such as in a multi-color rotogravure or flexographic printing line, it is often much more air per unit of solvent and the total exhaust mixture LEL concentration is relatively low.

Effective vapor capture sometimes requires more airflow than LEL safety considerations.

3. Vapor oxidation

Most common solvent vapours may be oxidized and converted into clean and harmless carbon dioxide and water vapor. However, chlorinated solvents can produce unpleasant hydrochloric acid vapors if they are oxidized.

Thermal oxidizers typically operate in the range of 1200 to 1500°F, with a hot gas hold time of 0.3 to 0.6 seconds to achieve essentially complete oxidation of organic materials.

Catalytic oxidizers typically operate several hundred degrees more than thermal oxidizers, depending on the specific catalyst used and the oxidation concentration of the vapor.

More expensive precious metal catalysts, such as platinum, will tolerate temporarily higher temperatures than less expensive catalysts that are susceptible to thermal deactivation. Some impurities in the air may poison any catalyst.

In some cases, the heat energy released by vapor oxidation can be used to heat a dryer or oven. Typically, the hot gas from the oxidizer is used to preheat the colder steam-containing air, and the waste heat is still sufficient for the treatment needs.

The cost of oxidizing a given dose of steam depends on how much dilution air is present, or how much steam is present for a given dose of air. More air requires a larger incinerator to keep the hot gas to the minimum time required to complete the oxidation reaction, and more energy is required to bring the air to the combustion (oxidation) temperature.

However, if the vapor concentration remains close to 40% LEL or higher, the solvent vapor can provide the full amount of energy required. At lower concentrations, it becomes increasingly necessary to provide auxiliary fuel or provide more air – air heat transfer to preheat air containing vapors.

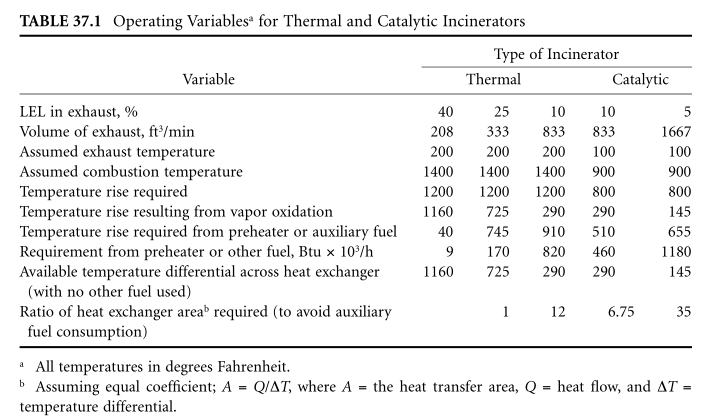

For example, one cubic foot of toluene vapor diluted with more or less air in the exhaust stream will be incinerated, as shown in Table 37.1.

As can be seen from Table 37.1, a reduction in the gas flow (for a given solvent vapor stream) will reduce the size of the steam incinerator in proportion, but the size of the heat exchanger or the amount of fuel that needs to be added is greatly affected.

Theoretically, sufficient heat exchanger capacity can be provided to avoid additional fuel for normal operation. In fact, an auxiliary fuel burner is required for starting, and when the vapor concentration decreases, it needs to remain ignited and ready to heat the air.

Heat exchangers used in steam thermal oxidizers are typically shell-and-tube type, using stainless steel tubes or ceramic beds. Some metal sheet-plate exchangers are also used, but in any case, it is important to prevent air containing vapors from leaking or shorting into the exhaust gases or bypassing the combustion area. This leak or bypass may produce an offensive odor from partially oxidized organics.

Ceramic bed heat exchangers operate by periodically reversing the direction of flow, passing through at least two or more alternating heated and cooled beds. The outgoing hot combustion gas flows through the bed until the ceramic sheet reaches the set temperature, and then flows in reverse, where the vapor-laden gas is heated and thus flows through the hot bed into the combustion zone. If the vaporized gas ignites in the bed before burning the space, but there is no problem before the flow switch, it is desirable to first purge the vapor-containing gas from the cooking bed into the combustion zone. Oxidation vapors should not be discharged. For relatively large beds, it is practical (but not cheap) to provide the high heat transfer area needed to accommodate the relatively thin vapor streams.

The required bed size can be minimized by high-frequency flow switching; The airtight damper can be switched every few minutes. Ceramic sheets need to be selected to withstand frequent temperature changes and to accommodate the thermal expansion-contraction cycles that occur. If dust is released through thermal movement or abrasion, it may prevent dryers and ovens from using residual hot gases directly.

Metal surface heat exchangers have hot combustion gases on one side and cooler vapor-containing gases on the other, and they work continuously with no flow reversal or opening and closing dampers. Thermal Expansion - Contraction can be a problem, causing welds or cracks to crack and allowing high-pressure vapor-containing air to leak into the low-pressure oxidation discharge stream. This leakage can produce an offensive odor through the evaporation of the steam.

In shell-and-tube heat exchangers, tubes with blocked counterflow are more effective than short tubes with crossflow.

A new development patented by Wolverine (Merrimac, MA) overcomes the expansion problem of long-tube heat exchangers; The tube can expand and contract freely at one end inside the slide tube that acts as an air aspirator. In this arrangement, a small amount of low-pressure oxidation vapor is allowed to leak back into the oxidation zone; Leaks in this direction are acceptable.

4. Solvent recovery

If the solvent can be reused, solvent recovery may take precedence over vapor oxidation, which allows the company to save a lot of money on the purchase of new solvents. Although vapor oxidation can recover some energy values from solvents, usually the "chemical" value is significantly higher than the energy value.

There are two important methods of solvent recovery: activated carbon and direct condensation.

The cost of the carbon method is much higher. Condensation methods are not always suitable, but can be much cheaper when dryers for coating the web and condenser are designed as a system.

1)Carbon adsorption

When carbon beds are installed to capture solvent vapors vented from the dryer, two or more carbon beds are typically supplied and periodically adsorbed from one while the other(sor) adsorbent is adsorbed.

Desorption is done by heating the bed and usually purging the steam with steam.

The steam and vapor then condense, and the vapor condensate (water) needs to be separated from the solvent. Typically about 3 to 4 or up to 10 pounds of steam per pound of solvent are recovered. If the recovered solvent is soluble in water (alcohols, ketones, etc.), there is an additional expense associated with the need to separate the water. Some vapors, such as methyl ethyl ketone, absorb onto carbon and release a lot of heat, and precautions need to be taken to prevent spontaneous combustion from causing combustion air to sweep the carbon bed.

There are many carbon adsorption systems where the value of recovered solvents outweighs the cost of operation. However, it is often more expensive to recycle the solvent than to buy a new one. In this case, the higher cost of recycling is to avoid air pollution.

2) Direct steam condensation

Direct vapor condensation is more economical than using a carbon bed for solvent recovery. Energy consumption is typically less than 10% of the energy required to run a conventional air purge dryer and carbon bed, and no water is added to the solvent in the process. Moreover, there is no exhaust gas flow to the atmosphere in the preferred design. Steam condensers are much smaller than those required for carbonization recovery systems, and another advantage is that separate steam condensers avoid the cost of mixing and separating solvents when two or more dryers are operating with different solvents or solvent mixtures. A chiller refrigeration system is usually required, but one system can be used for all condensers.

However, there are limitations to the suitability of this process: the process dryer needs to be essentially "airtight" in order to allow the contained atmosphere to circulate countless times and to exchange with the outside atmosphere with a minimum. Indirect heaters, such as steam coils, are necessary. In addition, the oxygen content in the contained atmosphere should be kept below the limit of being able to sustain combustion (10 to 13% O2), otherwise, it is necessary to use a very cold condenser and a relatively high recirculation rate to safely keep the vapor level below the steam LEL limit. A relatively small stream of inert (low oxygen content) gas is required to counteract the tendency of wet paper web to drag air into the dryer (21% O2) and it is necessary to maintain pressurized inertness (a) to facilitate rapid air purge and dryer start-up after the dryer has been turned on for any reason, and (b) to provide a safety pad for fail-safe shutdown during power outages.

The required inert (hypoxic) gas sources include flue gas from a gas-fired steam boiler and purchased liquid nitrogen or carbon dioxide. In the case of flue gases, the gas burner needs to be a fuel that can maintain a low excess air-fuel ratio at various fuel combustion rates. Compressors and booster tanks are available as backup tanks for final start-up and fail-safe shutdown, or liquid nitrogen tanks with vaporization facilities can be used.

In some important respects, the operation of an inert gas-tight dryer is inherently safer than that of a conventional purge dryer. In an air sweep dryer, there is a transition zone between the combustible moisture interface and the non-flammable exhaust, and excess solvents may be temporarily loaded into the dryer to produce large amounts of combustible mixtures. In an inerting dryer, there is no flammable interface, and any temporary excess solvent loading will not form a combustible mixture.

When the coating process and wet web are stopped for any reason, the outside air is not exchanged with the air contained in the dryer or to compensate for the shrinkage of the gas volume as the contained gas cools, except that air can be drawn in place of the condensed vapor volume. Inside

In a Wolverine system, the normal operating vapor concentration in the dryer is designed to prevent condensation caused by the amount of vapor generated by any unsafe air drawn into the dryer. Typically, the vapor condenser temperature is selected to reduce the vapor concentration to below the organic LEL level when the coating process is stopped. This provides a dual safety factor for safe O2LEL levels and safe organic air LEL levels.

When the dryer is turned off at night or on weekends, it is not necessary or desirable to clear the contained atmosphere to the outside atmosphere.

- 1Principle, application and selection of Electric Oven

- 2Principle, application and selection of Electric Oven

- 3Principle, application and selection of ozone sterilizing oven

- 4Principle, application and selection of tunnel oven

- 5Working principle and application analysis of laboratory oven

- 6Hot Air Oven FAQ and its solution

- 7Precision oven FAQ and its solution

- 8Oven FAQ and its solution

- 9How to calibrate the Drying Oven?