What are the advantages of in-line viscometers for viscosity testing?

There are many ways to measure viscosity, such as capillary, oscillatory and rotational. These methods have different advantages, and all may monitor the process well, but may obtain different test results from laboratory methods or analytical methods. Generally speaking, laboratory methods require more scientific and precise measurements, while process control requires stable and repeatable information. Process measurement consists of online and offline parts. Laboratory viscometers are often used to make off-line measurements, where a sample of the process fluid is extracted and tested under controlled conditions (temperature, shear history, shear rate, etc.). Inline viscometers are immersed in the process fluid, continuously measuring and monitoring under process conditions that help maintain consistent product quality. The requirements of the two environments are different, and it is unlikely that the same equipment will be used in both environments, nor will it be possible to have an identical test result. However, when done properly, test results will follow the same trends and remain correlated with laboratory results, making online measurements very useful for ensuring consistent product quality.

What benefits can online measurement bring to you?

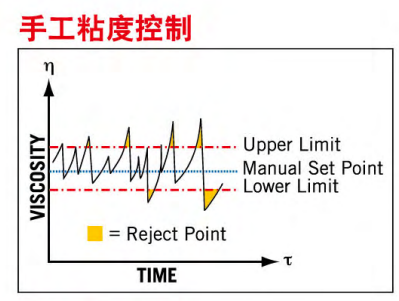

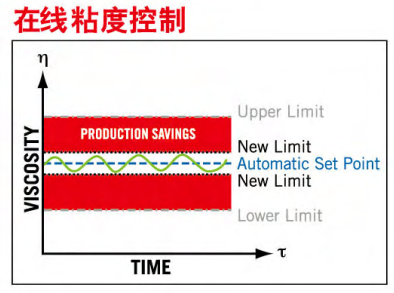

On-line measurement can provide real-time and continuous fluid viscosity readings in the process, and thus provides a method for automatically correcting process parameters and process fluid viscosity control. When it is difficult to control all the parameters affecting fluid viscosity in the process (such as temperature, air bubbles, shear history, eddy current, pressure change, etc.), if the parameters are kept relatively stable, a good control effect can be obtained.

How efficient is online measurement?

Automatic control of process fluid viscosity ensures consistent product quality and reduces or eliminates human error and costly sample testing. Moreover, it provides a complete record of process stage changes, rather than just a single point record.

What are the primary factors that need to be considered in online measurement?

For process measurements, the key factors are stability, repeatability and sensitivity to viscosity changes. The control of the analytical environment in the laboratory (such as temperature, flow, precipitation, air, etc.) and scientific measurement conditions (shear control, geometric shape of the measurement system and sample preparation) also need to be considered.

How to monitor the viscosity which affects product quality?

Most products are formulated to flow or disperse in a controlled manner. Viscosity is monitored at the critical shear point to ensure that the product performs well whenever the customer uses it. This is the most intuitive indicator of quality!

- 1Online Viscometer Selection Guide

- 2Selection method of Brookfield online viscometer

- 3Online Viscometer should be used correctly!

- 4Structure of Online Viscometer

- 5Testing Principles for Online Viscometers

- 6Nerun teaches you how to properly maintain an online Viscometer?

- 75 points to note when using online Viscometers

- 8Brookfield Online Viscometer Application in Oil/Gas Fields

Brookfield