Types of Viscosity Measuring Equipment: Viscometers and Rheometers

Viscosity—the resistance of a fluid to shear or tensile stress—is a desired measure in fluid analysis. Viscosity can be thought of as a resistance to flow, and fluids with high viscosity have more resistance to flow. Understanding the role of viscosity and measuring it is key to the proper analysis of many engineering situations. For example, using a lubricating fluid that becomes more viscous at high temperatures could have disastrous effects on a car engine. So sometimes it is important to be able to measure viscosity. Engineers can do this by using viscosity measurement equipment. Commonly used devices are viscometers and rheometers. This article describes the differences between the two devices and when using each.

U-tube viscometer

These viscometers are commonly used in laboratory environments. The user can obtain dynamic viscosity by measuring how long it takes a fluid to flow between two points in a capillary of known radius. The density of the fluid needs to be known to calculate the viscosity in this way.

Falling Ball Viscometer

As the name suggests, these viscometers use a falling ball to measure viscosity. The time it takes for a falling sphere of known density and radius to travel between two marks is measured, and the user can then calculate viscosity. This model is also commonly used in laboratories. They work on principles derived from Stokes' law, which applies drag to a sphere.

Falling Piston Viscometer

Piston-falling viscometers work similarly to ball-falling viscometers, except that they measure the resistance of a piston through a fluid. These devices have a long service life, are easy to operate and require little maintenance. Hence, they are very popular in the industry.

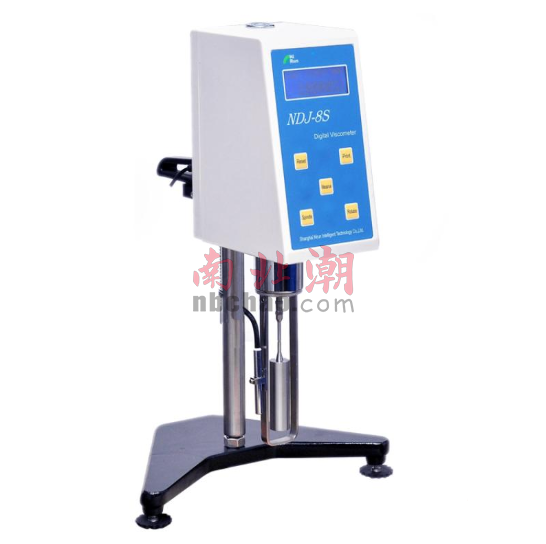

Rotational Viscometer

A Rotational Viscometer measures a fluid's resistance to torque. There are several types of Rotational Viscometers: the Stabinger viscometer was developed in 2000, while the Stormer viscometer is commonly used to measure the viscosity of coatings. Stabinger viscometers use a proprietary unit, the Krebs Unit (KU).

Bubble Viscometer

Bubble viscometers measure the time it takes air bubbles to rise through a liquid. These viscometers are often used with resins or varnishes. These viscometers are fast and very useful for on-site viscosity measurements. The model measured Stokes viscosity using the letter comparison method is 1 cm2s-1.

Rheometer

Rheometers are useful for non-Newtonian fluids. That is, the viscosity does not have a fluid described by a single value. Larger forces generally induce larger viscosities in non-Newtonian fluids. There are several commercial rheometers on the market. For forces below 10 Pa, ThermoFisher's CaBER is popular. Cambridge Polymers Group's FiSer is available for values from 1 to 1000 Pa, while Gottfert rheometers can be rated in excess of 100 Pa and Xpansion Instruments Sentmanat elongational rheometers can be rated in excess of 10 kPa.

Why measure viscosity?

Engineers may wish to measure viscosity in any application involving fluid flow, especially in design. Since viscosity can change dramatically with temperature, it is important to understand what happens to lubricants at high temperature, high pressure or low temperature. Failure to do so may result in design errors. Engineers developing new lubricants or other fluids may also wish to measure the viscosity of a fluid in a laboratory setting.

Field engineers may also need to measure viscosity. They can use any of the many portable viscosity Testers, or use larger industrial models to do this. Viscosity is important in many commercial applications, such as consumer products such as shampoo, and viscometers are widely used for quality control.

- 1Viscosity of polypropylene (PP) amide measured by NDJ Viscometer

- 2Which Viscometer to Choose for Licorice Extract Viscosity Testing? How to Test?

- 3Application of Rheometer in Viscosity Test of Tomato Paste

- 4Application of Rotational Viscometer in juice viscosity test

- 5Understanding Rheometers in One Article - Principle, Application, Selection & Maintenance

- 6Working Principle, Classification and Application of Capillary Viscometer

- 7Principle, Characteristics and Application of Dial Viscometer

- 8Basic Principle and Application of Ceramic Viscometer

- 9Principle, Characteristics and Application of QND Viscometer