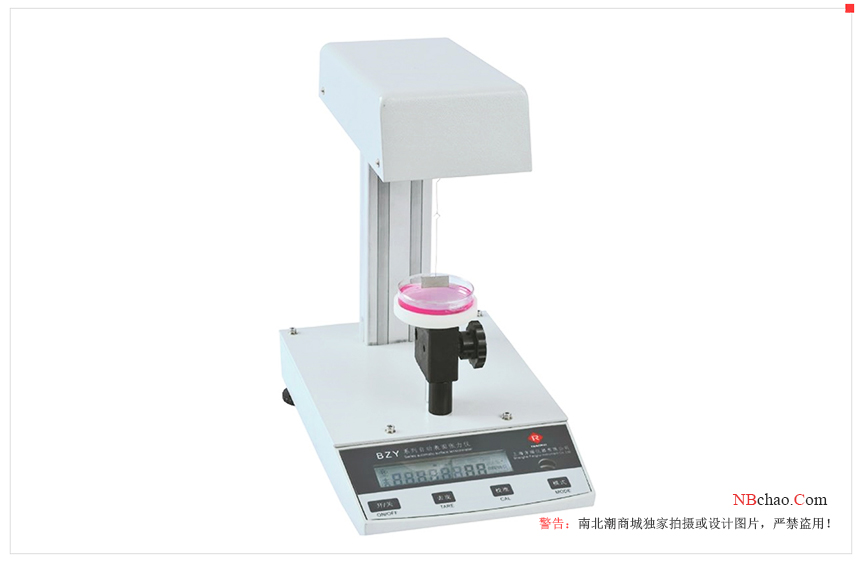

How to calibrate a surface tensIon Meter with a surface tension test solution?

Have you ever filled a glass with water so that the water level is higher than the glass and the water still remains in the glass? This seemingly gravity-defying observation suggests that there is a force that wants to keep the liquid together. This force is called surface tension.

Description of Surface Tension

Imagine an interface between a liquid and a gas. Most of the molecules in the two phases are in the host state, but some molecules are located at the interface facing the other phase. Molecules in the bulk interact similarly with all molecules around them – there is a similar pull in all directions, resulting in a net force of zero.

Instead, the molecules at the interface exert stronger pulls on the bulk of their own phase. The net force that effectively holds a liquid together is called surface tension.

What is the unit of surface tension?

Mathematically, surface tension is the force expressed by the intermolecular force divided by the length of the contact line between phases. Therefore, the unit of surface tension is N/m. The force is usually so small that mN/m has become the standard unit used. For example, water has a relatively high surface tension of 72 mN/m at room temperature due to its strong hydrogen bonds.

Many methods of measuring surface tension are also based on direct measurement of the force exhibited by the surface tension of each measuring probe.

- 1Working principle of mechanical liquid meter interfacial tensIon Meter

- 2Comparison of Liquid Surface/Interfacial Tension Testing Methods: Plate vs. Ring Method

- 3Selection guide for Surface Tensiometers

- 4Application principle and precautions of platinum ring Surface Tensiometer

- 5Analysis of the difference between contact angle meter and Surface Tensiometer

- 6The working principle, application and operation steps of surface tensIon Meter

- 7Fangrui surface tensIon Meter test data deviation, how to solve?

- 8Comparison of Fangrui's different series of automatic watch interfacial tensIon Meters

- 9What is the measurement principle of surface tension?