Rheology and its importance in coating applications

Rheology is the fundamental study concerned with the flow or deformation of substances under the action of external forces, and in the context of chemical coatings, mainly concerns the flow of liquids or semisolids.

This is in contrast to viscosity, a branch of rheology that deals with a substance's resistance to flow as a function of time and temperature. In the context of coatings science, this can be seen as the frictional resistance of an object as it passes through the solvents and polymers (with constant strain rates) that make up the coating system. Rheology and viscosity are distinguished by viscosity, which is a measure of resistance to flow. Viscosity is also expressed as the relationship between shear rate and shear stress, ie shear stress divided by shear rate.

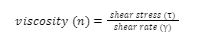

Shear stress (τ) can be defined as a measure of the force (F) applied to an area of interest (A) (such as a layer of paint beneath a brush or agitator, Figure 1). Shear stress applied to this region induces deformation, which is defined as the shear strain of the material.

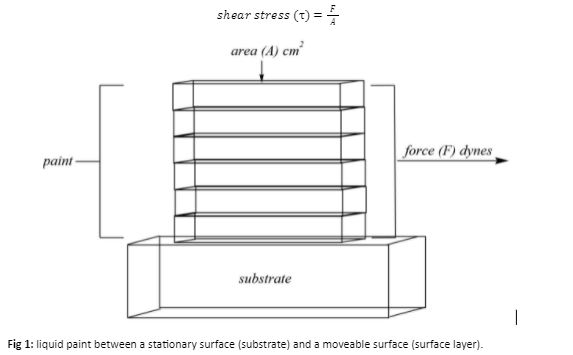

The shear rate can be defined as a measure of the resulting velocity gradient, which depends on the speed at which the top layer moves (V) and the thickness of the layer between the surface and the substrate (T) (Fig. 2). Velocity can also be seen as the change in strain (speed of stirring or brushing in a paint system) over time.

In terms of coating chemistry, rheology affects performance and thus has a major impact on the overall coating system. These include but are not limited to:

Resin and paint transfer/shipping.

Pigment Dispersion

paint application

Film formation and film coalescence

Storage and long-term stability (soft and hard settling of pigments and fillers

In terms of the properties of the final coating system, many of these are influenced by rheology, including:

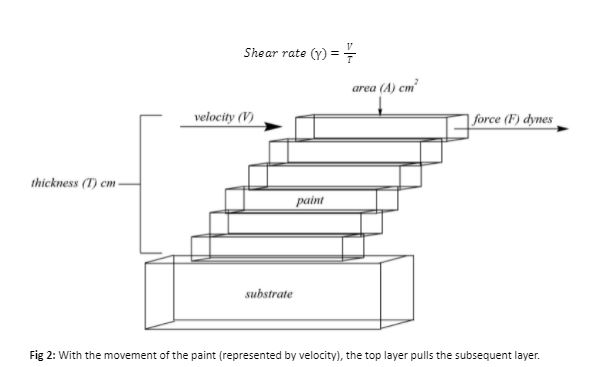

Flow and leveling (for self-leveling and texturing systems)

Anti-sag and vertical wall applications

Type of paint application (spray, roller or brush)

film thickness

Adhesion

Opacity

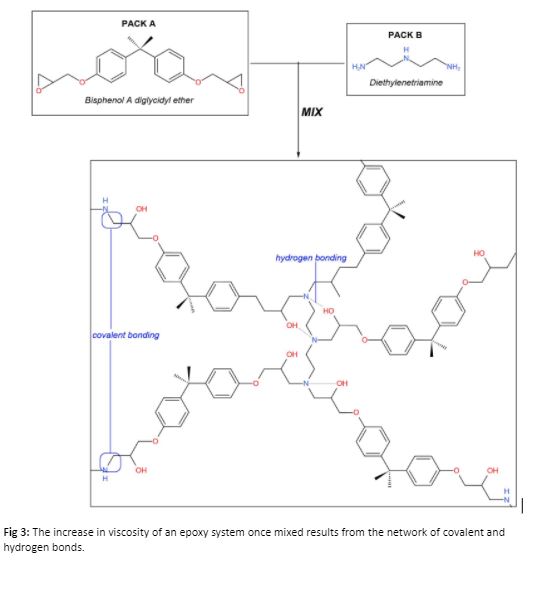

On a chemical level, viscosity can be the result of molecular interactions, including covalent and ionic bonds, coordination complexes (primary and secondary (ligand) valences), and hydrogen bonds. When a coating system begins to cure (or react under specified conditions), such as a 2-pack epoxy/polyamine system (Figure 3). Once the amine hardener encounters the epoxy resin and reacts via nucleophilic ring opening, the viscosity of the resulting polymer network generally increases due to the increase in covalent and hydrogen bonding of the system.

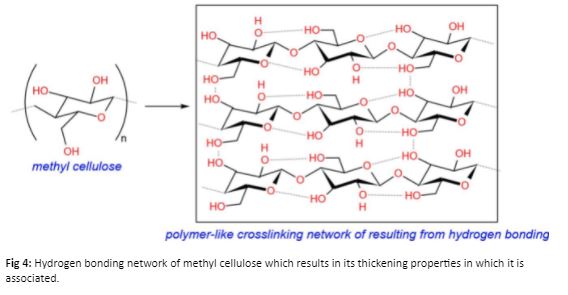

A typical example of a thickener used in paint systems is a cellulose derived thickener. These thickeners take advantage of the high polarity and hydrogen bonding of the cellulose network to provide higher viscosity to the overall coating system (Figure 4).

In addition to molecular interactions, many other factors determine the rheology of a coating system, including:

Resin solubility and compatibility with other ingredients such as resins, fillers, additives, etc.

Solvent content and chemical properties such as polarity

Pigments and fillers

Additives (wetting, dispersing, anti-sedimentation, etc.)

These factors can be used to control the overall rheology of the coating system without negatively impacting the desired properties of the final cured coating.

In summary, rheology describes the overall behavior of a system when a force is applied and is directly related to the properties of a coating system. Different types of coatings are exposed to specific shear rates during production and manufacturing, so there is no universally optimal rheology for any application, each coating needs to be engineered for a specific coating.

- 1Paint transparency detection method

- 2Coating rheology and thixotropic

- 3Coating unit talk

- 4Coating gloss detection solution

- 5What coating defects can be avoided by testing the surface tension properties of coatings?

- 6Measuring Color Difference in the Coatings Industry

Cheryl Roberts

- 7Classification of coatings

- 8The role of paint and film formation method

- 9What is the difference between paint and paint?